A brief insight into the history of a place before visiting it is always a prerequisite for a more meaningful and interesting tour and in Sarawak’s case, it is no exception.

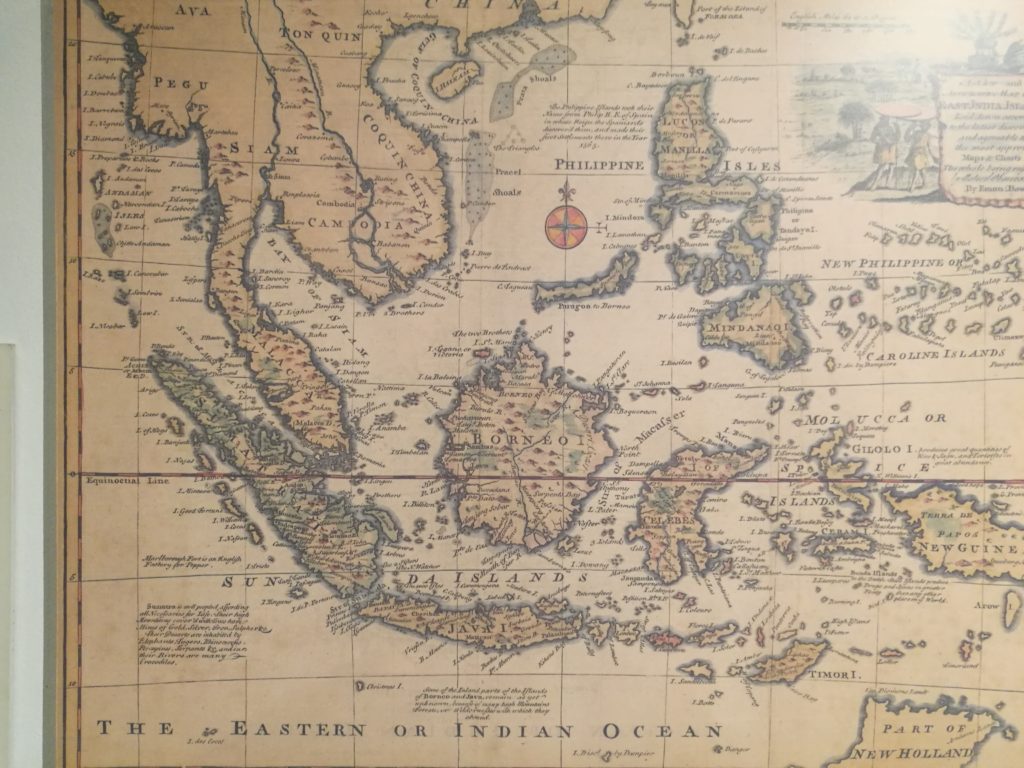

Since the early 1500s Sarawak was already recorded in European maps. Then the coastal areas between Tanjung Datu and Brunei Bay were territories claimed by the powerful Sultanate of Brunei, which stationed administrators in outposts like Kuching and the coastal area where Malay people predominated. The interior of Sarawak then had sparse population consisting of scores of tribes, chief among whom were the Iban, the Bidayuh, the Kenyah, the Kayan and so on. As Brunei was far away, and there was practically no means of transport except by rivers and seas, its rule can only be described as loosely binding at best and non-existing at worse. as such many interior tribes were openly rebellious given their warlike nature and their dreaded tradition of headhunting.

In 1839, an Englishman, fortune-seeker and adventurer, James Brooke sailed into the Sarawak River with his armed yacht, and found the region in the midst of a long-running revolt. Raja Muda Hashim, a Brunei prince sent by the Sultan to oversee the quelling of the rebels, pleaded Brooke, with his superior fire-power and gunboat to help him put down the rebellion and dangled the governorship of Sarawak as the prize. Brooke must have seen this as an opportunity to gain a foothold and thus readily agreed. As expected, the Englishman completed the task but the promised prize was not formalized after much foot-dragging by Brunei until 1841, when he was declared the Rajah of Sarawak. Thus began the 100-year rule of Sarawak by James Brooke and his successors, nephew Charles Brooke and Charles’ son Charles Vyner Brooke as the second and third Rajah respectively, until at the outbreak of the Pacific War when Kuching was invaded by the Japanese forces on Christman Day 1941.

Raja Muda Hashim, the Brunei prince who was sent to Sarawak to oversee the suppression of the native revolt

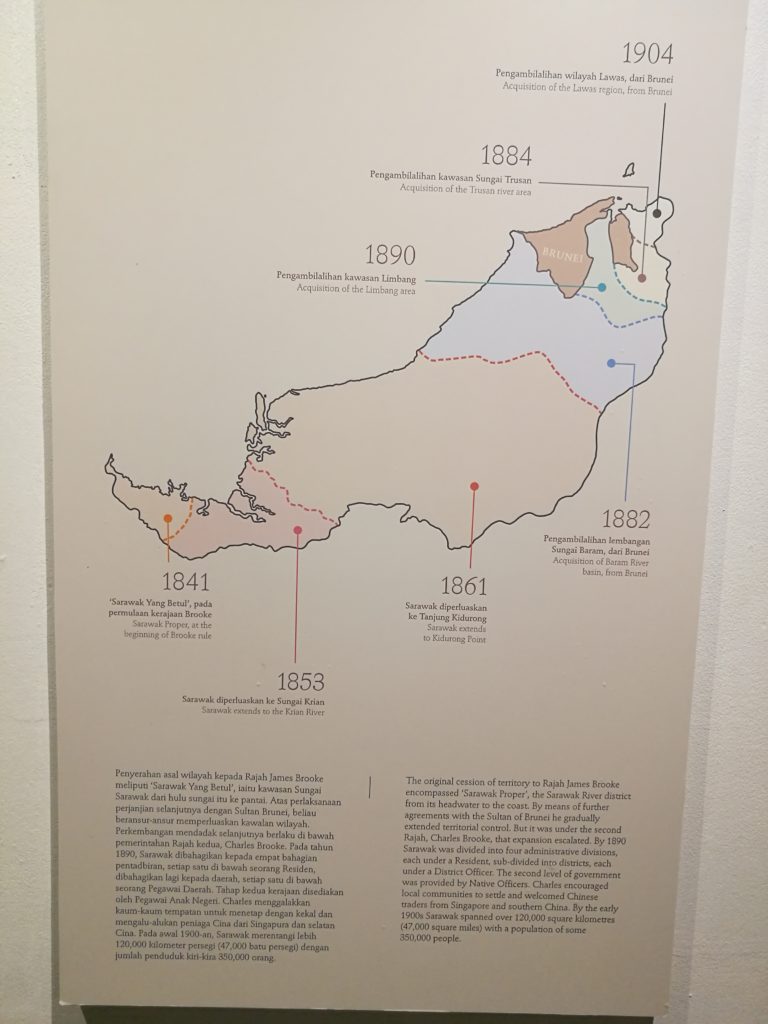

When he took over the country, the fledgling town of Kuching already had Chinese and some Indian traders along the present day Gambier Street and other parts of town. James Brooke set about establishing an administrative machinery by recruiting his countrymen as the top echelon of the civil service. He astutely gained the confidence and support of the local Malays and was rewarded with their unflinching loyalty throughout his family’s rule. Then he made allies with the fractious interior tribes in a divide-and-rule strategy. This was to counter the other warlike tribes at the fringe of his territory. In fact, war expeditions to “punish” the latter became a regular part of the first and second Rajahs’s rule. This often also resulted in increased territorial acquisitions, where the size of Sarawak grew larger and larger over the years at the expense of the Brunei Sultanate, with the final borderline just outside of Brunei’s capital by the start of the 20th century. Brunei, then a spent force, could only helplessly signed away territory after territory, to the relentless march of an aggressive family-owned country called Sarawak. Brooke’s exploits in pitting one tribe against another in his so-called punitive expeditions often resulted in great loss of lives and minimal loss to his own force, thus gaining wide notoriety back in Britain, and was a much reviled personality despite being knighted by Queen Victoria. Noteworthy was the massacre in 1857 of over 3,000 (by a present day historian’s reckoning) rebellious Chinese miners and their families from Bau, a gold mining town outside of Kuching.

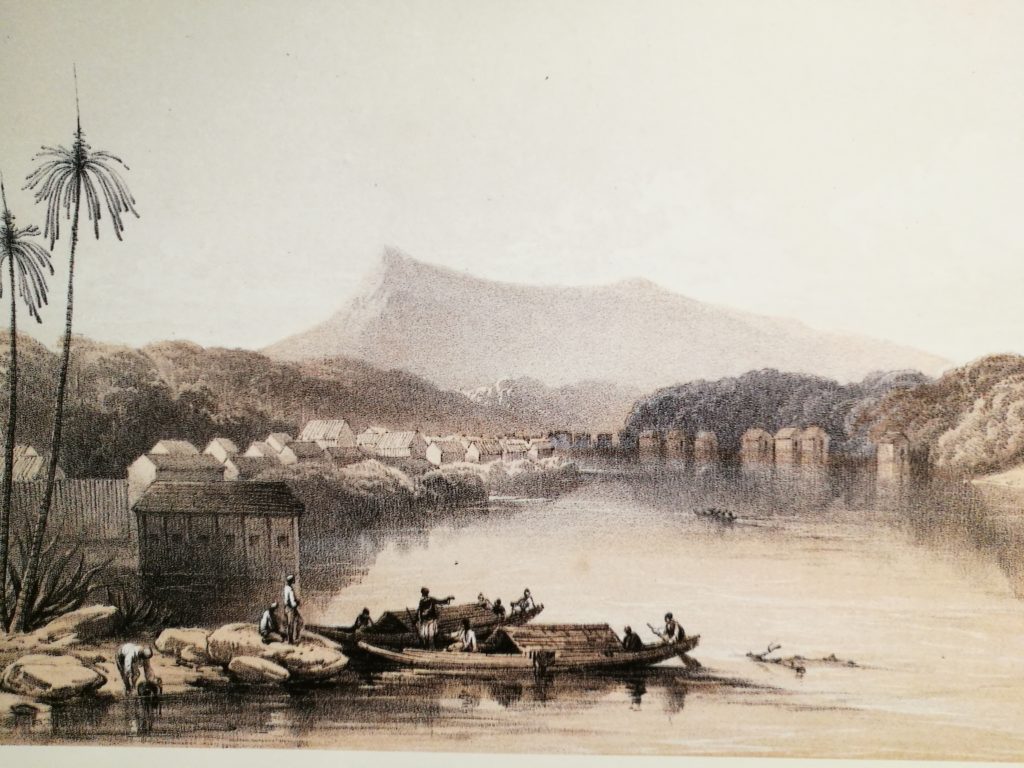

The town of Kuching in 1847 as viewed from present-day Waterfront with the Matang mountain range in the background.

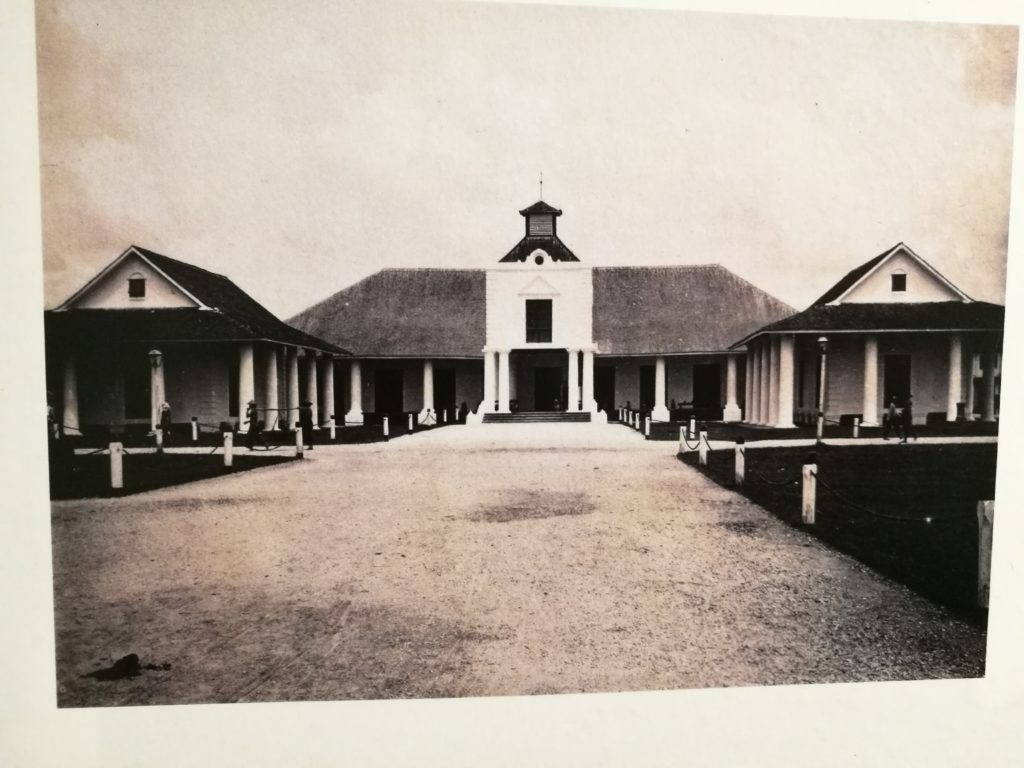

However, many also welcomed the change in the governance the Brookes established, as a proper rule of law brought relative peace and was good for a stable environment. All the three Rajahs built buildings that were European in appearance in the middle of town, which makes Kuching an exotic mix of Victorian and turn-of-the-century South East Asian architectural marvel. The old quarter of Kuching abounds with buildings like the Astana, or the “palace” of the Rajah, Fort Magherita, the Square Tower, the Round Tower, the Pavilion, the General Post Office, the Sarawak Museum and the Old Court House, among others, and most are right next to the old Chinese shophouses and temples, along Carpenter Street, Main Bazaar, India Street and Gambier Street.

The century rule of the Brooke family is nothing short of extraordinary, for it was not a British colony in the mould of Penang, Singapore or Malacca. Rather this was a one-of-its-kind of fiefdom where an English family held absolute power, whose words were actually the law, including the power of life and death over his subjects. Sarawak’s locale in the middle of a territory peopled by savage headhunters tribes, hot and uninhabitable tropical forests and its pirate-infested coastline and seas, made it hardly the place to settle down let alone where fortune could be made. But settle down the Englishmen did. The eclectic mix of European administrators, Christian missionaries, Chinese traders and gold miners, savage natives, pirates roaming the high seas in no less an exotic island of 19th century Borneo provides the perfect ingredients for the romances which later spawned the classics by Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad and Somerset Maugham among many others. James Brooke and to a great extend his nephew, Charles, are the classic examples of the phrase “Mad dog and Englishmen”. In fact the story of the Brookes, especially James and Charles provided the inspirations for scores of authors to pen books (just google them!) that read more like fictions than real-life adventures, and herein lies one of the great allures of Sarawak: its romantic history.

The growth of Sarawak at the expense of Brunei, from a small territory surrounding Kuching in 1841 to its final border in 1904.

During the Pacific War, Kuching also saw some actions, as it was the administrative centre of British-friendly Sarawak. The Japanese invaded Kuching on Christmas Day 1941 and held it until its liberation by the Allied Forces in September 1945. Kuching was also the site of the notorious Batu Lintang Internment Camp, where at one time, over 3,000 Allied prisoners of war, mostly Australian soldiers, and local European civilians and their families were interned. Many of the exploits and sufferings of the internees are vividly described in the now famous novel Three Came Home, by Agnes Keith, wife of an American military personnel then stationed in Borneo.

After the War, the last Rajah, who fled to Australia at the start the War, decided to cede the ruined country to Britain in exchange for a tidy royalty and retired to England. Sarawak became a crown colony of Britain, but not everybody was happy. Loyalist Malays clamoured for the return of the Brooke rule, with the heir-apparent Anthony Brooke (Vyner Brooke’s nephew) leading the charge but to no avail. By the early 60s, a proposal was made by Tunku Abdul Rahman of the Federation of Malaya, which had earlier gained independence from Britain in 1957, to unite the other 3 entities viz. Singapore, Sarawak and Sabah into a single country called Malaysia. After much negotiations, discussions and even a referendum Malaysia was born on 16th September 1963. But by August 1965, just 2 years later, Singapore left the Federation. Brunei had earlier opted not to join.

With her abundant natural resources of oil and gas, timber, agricultural produce and land, Sarawak was able to develop quickly under Malaysia and continues to do so with its population of 2.7 million of multi-ethnicities spreading over an area of 48,000 square miles. Many cities and towns like Kuching, Miri, Sibu and Bintulu have developed beyond recognition even compared to a decade or two ago with many highways and high-rise buildings. Moving farther away from towns and cities, development may not be so obvious, but the livelihood of the rural people are definitely much better than in the olden days.